Motor Vehicle Crashes

and Low Back Pain

Physical events in a gravity environment have always caused injuries. The mathematics and physics of these injuries were not formalized until the year 1687 when Sir Isaac Newton wrote the book Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy (1). In this publication, Newton details the principles of inertia.

Inertia is the resistance of a physical object to any change in its state of motion or to its state of rest. An object in motion will remain in motion unless an outside force acts upon that object. Likewise, an object at rest will remain at rest unless an outside force acts upon that object.

These Laws of Inertia apply to the human body. Different parts of the human body have different inertias between them. It is these inertial differences between the different parts of the body that increase their risk of injury.

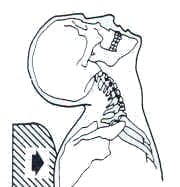

The greatest inertial difference in the body is between a human’s trunk and head. The neck (cervical spine) connects these two distinct inertial masses and therefore the neck has a great vulnerability to injury.

The incidence of inertial injury to the cervical spine has dramatically increased with advances in wheeled transportation. Whatever the wheeled transportation, the person is probably sitting in the vehicle. All quick movements of the vehicle will also move the trunk of the person sitting in the vehicle. Since the trunk inertia is separate from head inertia, the neck is vulnerable to inertial injury.

Trunk Movement Neck Inertial Injury

An early scientific/medical publication describing cervical spine inertial injuries caused by wheeled vehicle accidents was published in 1867, titled (2):

On Railway and Other Injuries of the Nervous System

As noted in the title, these injuries were from train accidents, occurring decades prior to the first automobiles.

Within a few decades of automobiles becoming commonplace in the society, cervical spine inertial injuries also became commonplace. In 1928, physician Harold Crowe, MD, presented a lecture at the Western Orthopedic Association convention in San Francisco, CA. In his presentation he introduced the word “whiplash” to describe these cervical inertial injuries, and the terminology is still standard today (3, 4).

Cervical spine inertial injuries from motor vehicle crashes are well documented and accepted. They are well described in reference texts pertaining to whiplash injuries (5, 6, 7).

However, it is much more controversial as to whether motor vehicle collisions can cause injury to the low back. The mechanisms for these low back injuries are poorly understood and therefore such injuries are often viewed with skepticism or rejected. Yet, this topic has been explored for decades and a number of studies have quantified their incidence.

It is established that the primary reason people go to chiropractors is for low back pain (63%), and the level of satisfaction from this chiropractic care is very high (8). Spinal manipulation and chiropractic have a long history of successful clinical outcomes for treating low back pain (9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15).

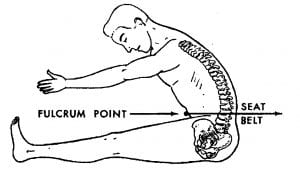

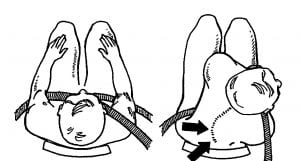

Early documented cases of low back injury during motor vehicle collisions involved the restraint devices, primarily lap seat belts (16, 17, 18, 19, 20).

The lap belt, when used alone, does not stop the forward inertial motion of the trunk above the belt or the pelvis and legs below the belt. Lap belts concentrate the inertial forces to the small cross-sectional dimension of the belt, allowing the belt to function as a fulcrum. The stresses at the fulcrum (the belt) are magnified, resulting in increased injury to the tissues behind the lap belt. This includes a flexion-type injury to the low back.

The addition of a unilateral shoulder harness will further introduce a rotational component of stress to the low back (21). This combination of low back flexion and rotation increases the risk of low back injury.

(From #21)

Other mechanisms (other than restraint device use) of low back injury caused by motor vehicle collisions may occur. Some of these are mentioned in the studies reviewed below.

Over the decades, a number of medical/scientific studies have attempted to quantify the incidence of low back injury from motor vehicle collisions:

- In 1994, a study from Iceland was published in the journal Cephalalgia and titled (22):

Extra-Cervical Symptoms After Whiplash Trauma

The study involved 38 patients with chronic whiplash syndrome. They were investigated with regard to symptoms that could be confirmed with the criteria for a specific diagnosis:

- 65.8% were women

- 34.2% were men

- Ages were 17 to 52 years with a mean 33 years

- Time from accident to investigation was 6 to 44 months (mean 17 months)

All patients had been healthy before the accident and had sustained a whiplash injury without head injury, and had no signs of radiculopathy or myelopathy.

The authors found that 47.7% of the patients complained of low back pain, and that 13.2% were diagnosed with chronic mechanical low back pain. Importantly, 5.3% were diagnosed with segmental instability of the lumbar spine. The authors state:

“Reported incidence of low back pain (LBP) after whiplash injury is 40-60%, and the incidence of 47.7% in the present study is in concordance with these earlier results.”

“Mechanical injury to the low back can be caused by the initial extension of the low back followed by flexion when the pelvis and the legs are thrown forward while the body is held in place by the safety belt or stopped by the steering wheel.”

- A 2001 study from Sweden was published in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology and titled (23):

The Association Between Exposure to a

Rear-End Collision and Future Health Complaints

Over a period of 7 years, the authors compared 232 whiplash-injured patients to 204 subjects who were involved in motor vehicle crashes but not injured. Both groups were compared to 4,088 control subjects.

The whiplash-injured patients had an increased risk of low back pain at 7 years by 270% compared to the other groups.

- In 2002, an American study was published in the American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation and titled (24):

Lumbar Spinal Strains Associated with Whiplash Injury:

A Cadaveric Study

The authors note that up to half of those involved in a whiplash accidents may develop low back pain. Therefore, they measured the forces on the lumbar spines of human embalmed cadavers subjected to a number of low speed vehicle collision events.

These authors proved that there are both horizontal and vertical spinal forces that result from a strictly horizontal force applied experimentally. The authors state:

“Frequently, seemingly implausible claims of lumbar injuries are mentioned after low-speed rear-end collisions, even when little vehicular damage is reported.”

“Apparently, rear-end collisions lead to soft-tissue injuries with paucity of findings on physical examination, negative radiograph studies, profuse symptomatology, and prolonged disability.”

The forces generated during simulated whiplash collisions induce biphasic lumbar spinal motions (increased-decreased lordosis) that “may be sufficient to cause soft-tissue injuries.”

- A 2003 study from Canada was published in the journal Spine and titled (25):

Low Back Pain After Traffic Collisions:

A Population-Based Cohort Study

The study is a population-based, incidence cohort study involving 4,473 subjects. The authors concluded:

“Low back pain is a common traffic injury with a prolonged recovery.”

- In 2010, a study from the United Kingdom was published in the journal Injury and titled (26):

Can Patients with Low Energy Whiplash Associated Disorder

Develop Low Back Pain?

The study analyzed 800 consecutive patients for symptomatology of whiplash injury including the presence of low back pain. The authors found that back injury occurred in approximately 40% of the subjects. These injuries occurred in all directions of impact (rear, frontal and side impact), and these injuries occurred in low, medium and high levels of collision impacts. Almost all of these subjects with low back injury also injured their necks, and the majority of them had a past medical history of back pain. The authors stated:

“We were surprised that patients with next to no car damage had the same incidence of back pain as those involved in more violent crashes when biomechanically unlikely.”

- Another Canadian study was published in 2010 in the Journal of Occupational Environmental Medicine and titled (27):

Whiplash Injury is More than Neck Pain:

A Population-Based Study of Pain Localization after Traffic Injury

This study was a cross-sectional analysis of a cohort of 6,481 patients, and 60% were found to have low back pain.

- Again in 2010, the Society of Automotive Engineers published a study titled (28):

Lumbar Loads in Low to Moderate Speed Rear Impacts

The authors note that although most of the research on vehicular rear impacts has focused on the neck, there is currently increasing concern about the lumbar spine. They produced a series of low impact collisions involving anthropomorphic test devices and measured the stresses imparted to the lumbar spines. The authors concluded:

The lumbar spines may experience overall compressive and bending loads.

“Spinal bending superimposed with sudden spinal compression has been suggested as a mechanism of creating acute herniations on the rare occasion in which low back pain associated with an intervertebral disc herniation was reported.”

“The spine might experience some transient bending and compression, which could be consistent with the proposed mechanism of acute disc herniation.”

- A 2011 study from Norway was published in the journal BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders and titled (29):

Headache and Musculoskeletal Complaints Among Subjects

with Self-Reported Whiplash Injury

This study was a cross-sectional study on 59,104 subjects. The authors found a positive association between a history of a whiplash injury and low back pain in both men and women. The increased risk in men was 210%. The increased risk in women was 380%.

- A 2013 study from Japan was published in the European Spine Journal and titled (30):

Prevalence of Low Back Pain and Factors Associated

with Chronic Disabling Back Pain in Japan

This was a cross-sectional survey in Japan on 65,496 adults. It found a positive association between a traffic injury and chronic disabling low back pain. Specifically, motor vehicle crashes increased the risk of low back pain by 181%.

- A 2014 study from the United States (Massachusetts, Florida, Michigan, and New York) was published in the journal Pain and titled (31):

Pain Location and Duration Impact Life Function Interference

During the Year Following Motor Vehicle Collision

The study involved a cohort of 948 patients who had initially been seen in the emergency department and subsequently assessed a year later. The authors found that 37% of the patients had moderate or severe low back pain. The author stated:

“Pain across all body regions accounted for nearly twice as much of the variance in pain interference as neck pain alone. These findings suggest that studies of post-MVC pain should not focus on neck pain alone.”

- In 2018, a Canadian study was published in the European Spine Journal and titled (32):

The Association Between a Lifetime History of Low Back Injury

in a Motor Vehicle Collision and Future Low Back Pain:

A Population-Based Cohort Study

The purpose of this population-based cohort study of 789 subjects was to investigate the association between a lifetime history of a low back injury in a motor vehicle collision (MVC) and future troublesome low back pain. Troublesome LBP was measured at 6 and 12 months following the MVC.

The authors found that in those with a history of low back pain, MVC injury increased the development of future troublesome LBP by 176%. The authors stated:

“LBP is common after a motor vehicle collision.”

“This study supports prior research on the hypothesis that a past history of a low back injury in a MVC may be a determinant of future LBP.”

“Our analysis suggests that a history of low back injury in a MVC is a risk factor for developing future troublesome LBP.”

“Our analysis provides the public, clinicians, government and insurers with evidence that a low back injury in a MVC may have a role in the development of future low back pain.”

“The consequences of a low back injury in a MVC can predispose individuals to experience recurrent episodes of low back pain.”

- In 2019, another Canadian study, published in the journal Traffic Injury Prevention and titled (33):

Low-Velocity Motor Vehicle Collision Characteristics

Associated with Claimed Low Back Pain

The objective of this investigation was to characterize the physical circumstances of low-velocity motor vehicle collisions that resulted in claims of low back pain (LBP). The authors assessed 83 injury cases.

The study found that 77% of the cases reported low back pain. The authors state:

“The most common pre-existing medical condition was prior LBP or evidence of disc degeneration.”

“It was found that pre-existing LBP and lumbar spine disc degeneration were particularly common in those with LBP.”

“The development of future LBP is higher in individuals with a past self-reported low back injury resulting from a motor vehicle collision compared to those without.”

This data set showed a “very high correlation between LBP claims and WAD claims.”

“These observations point to the likelihood of the rear-end impact crash configuration being a relevant factor in LBP reporting.”

“For individuals with a history of LBP, the risk of redeveloping LBP doubles, putting these individuals at greater risk of reporting LBP in the future.”

As noted, many studies have investigated the incidence of low back pain following motor vehicle crashed. These studies span many decades, multiple scientific journals, and multiple countries. Collectively, they involve tens of thousands of subjects. They all conclude that motor vehicle crashes do increase the risk of low back injury and pain. Any suggestion that motor vehicle crashes cannot cause low back pain appear to be in error, or perhaps self-serving. Chiropractors should be confident that complaints of low back pain following vehicle crashes are credible, and treatment is reasonable, necessary, and appropriate.

References:

- Newton I. Principia Mathematica; July 5, 1687.

- Erichsen JE; On Railway and Other Injuries of the Nervous System; Philadelphia, PA; Henry C. Lea; 1867.

- Crowe H; A New Diagnostic Sign in Neck Injuries; California Medicine; January 1964; Vol. 100; No. 1; pp. 12-13.

- Todman D; Whiplash Injuries: A Historical Review; The Internet Journal of Neurology; Vol. 8; No 2; 2006.

- Jackson R; The Cervical Syndrome; Thomas; 1978.

- Foreman S, Croft A; Whiplash Injuries: The Cervical Acceleration/Deceleration Syndrome; Williams & Wilkins; 1988.

- Cailliet R; Whiplash Associated Diseases; American Medical Association; 2006.

- Adams J, Peng W, Cramer H, Sundberg T, Moore C; The Prevalence, Patterns, and Predictors of Chiropractic Use Among US Adults: Results From the 2012 National Health Interview Survey; Spine; December 1, 2017; Vol. 42; No. 23; pp. 1810–1816.

- Edwards BC; Low back pain and pain resulting from lumbar spine conditions: a comparison of treatment results; Australian Journal of Physiotherapy; Vol. 15; 104; 1969.

- Kirkaldy-Willis WH; Managing Low Back Pain; Churchill Livingston; (1983 & 1988).

- Kirkaldy-Willis WH, Cassidy JD; Spinal Manipulation in the Treatment of Low-Back Pain; Canadian Family Physician; March 1985; Vol. 31; pp. 535-40.

- Meade TW, Dyer S, Browne W, Townsend J, Frank OA; Low back pain of mechanical origin: Randomized comparison of chiropractic and hospital outpatient treatment; British Medical Journal; Vol. 300; June 2, 1990; pp. 1431-7.

- Stern PJ, Côté P, Cassidy JD; A series of consecutive cases of low back pain with radiating leg pain treated by chiropractors; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; 1995 Jul-Aug; Vol. 18; No, 6; pp. 335-342.

- Giles LGF; Muller R; Chronic Spinal Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial Comparing Medication, Acupuncture, and Spinal Manipulation; Spine July 15, 2003; Vol. 28; No. 14; pp. 1490-1502.

- Muller R, Giles LGF; Long-Term Follow-up of a Randomized Clinical Trial Assessing the Efficacy of Medication, Acupuncture, and Spinal Manipulation for Chronic Mechanical Spinal Pain Syndromes; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; January 2005; Vol. 28; No. 1; pp. 3-11.

- Chance GQ; Note on a type of flexion fracture of the spine; British Journal of Radiology; September 1948; Vol. 21(249); p. 452.

- Marsh HO, Bailey D; Seat Belt fractures: Chance fractures caused by seat belts: Presentation of three cases; J Kans Med Soc; September 1970; Vol. 71; No. 9:361-365.

- Rogers LF; The roentgenographic appearance of transverse or chance fractures of the spine: The seat belt fracture; Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med; April 1971; Vol. 111; No. 4; pp. 844-849.

- Rutherford WH; The Medical Effects of Seat-Belt Legislation in the United Kingdom: a critical review of the findings; Archives of Emergency Medicine; 1985; Vol. 2; pp. 221-223.

- Thompson NS, Date R, Charlwood AP, Adair IV, Clements WD; International Journal of Clinical Practice; Seat-belt syndrome revisited; October 2001; Vol. 55; No. 8; pp. 573-5.

- Anrig C, Plaugher G; Pediatric Chiropractic; Williams & Wilkins; 1998.

- T Magnússon T; Extra-cervical Symptoms After Whiplash Trauma; Cephalalgia; June 1994; Vol. 14; No. 3; pp. 223-227.

- Berglund A, Alfredsson L, Jensen I, Cassidy JD, Nygren Å; The association between exposure to a rear-end collision and future health complaints; Journal of Clinical Epidemiology; November 2001; Vol. 54; No. 11; pp. 851–856.

- Fast A, Sosner J, Begeman P, Thomas MA, Chiu T; Lumbar Spinal Strains Associated with Whiplash Injury: A Cadaveric Study; American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation; September 2002; Vol. 81; No. 9; pp. 645-650.

- Cassidy JD, Carroll L, Cote P, Berglund A, Nygren A; Low Back Pain After Traffic Collisions: A Population-Based Cohort Study; Spine; May 15, 2003; Vol. 28; No. 10; pp. 1002-1009.

- Beattie N, Lovell ME; Can patients with low energy whiplash associated disorder develop low back pain?; Injury; February 2010; Vol. 41; No. 2; pp 144-146.

- Hincapie C, Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ, Cote P, Guzman J (2010); Whiplash injury is more than neck pain: a population-study of pain localization after traffic injury; Journal of Occupational Environmental Medicine; Vol. 52; No. 4; pp. 434–440.

- Gates, D, Bridges, A, Welch, T, Lam, T et al.; Lumbar Loads in Low to Moderate Speed Rear Impacts; SAE Technical Paper 2010-01-0141, 2010.

- Myran R, Hagen K, Swebak S, Nygaard O, Zwart JA; Headache and musculoskeletal complaints among subjects with self-reported whiplash injury: the HUNT-2 study; BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders; June 8, 2011; Vol. 12:129.

- Fujii T, Matsudaira K; Prevalence of low back pain and factors associated with chronic disabling back pain in Japan; European Spine Journal; Vol. 22; No. 2; pp. 432–438.

- Bortsov AV, Platts-Mills TF, Peak DA, Jones JS, Swor RA, Domeier RM, Lee DC, Rathlev NK, Hendry PL, Fillingim RB, McLean SA; Pain Location and Duration Impact Life Function Interference During the Year Following Motor Vehicle Collision; Pain; September 2014; Vol. 155; No. 9; pp. 1836-1845.

- Nolet PS, Kristman VL, Cote P, Carroll LJ, CassidyJD; The Association Between a Lifetime History of Low Back Injury in a Motor Vehicle Collision and Future Low Back Pain: A Population-Based Cohort Study; European Spine Journal; January 2018; Vol. 27; No. 1; pp. 136–144.

- Fewster KM, Parkinson RJ, Callaghan JP; Low-Velocity Motor Vehicle Collision Characteristics Associated with Claimed Low Back Pain; Traffic Injury Prevention; 2019; Vol. 20; No. 4; pp. 419-423.

“Authored by Dan Murphy, D.C.. Published by ChiroTrust® – This publication is not meant to offer treatment advice or protocols. Cited material is not necessarily the opinion of the author or publisher.”